Changing jobs is a tricky thing. On the one hand, as you lead up to that decision, you are probably getting tired of what you are doing, and the idea of a change starts seeping into your thoughts. On the other, there’s the idea that a promotion or new opportunity is just around the corner if you stay.

So you go back and forth: stay where you know the territory? Or move on and start something newer and potentially better? Both are complete unknowns.

A change decision is pretty easy when you are single. Anything you decide is something only you have to deal with. Get married and have a family, the decisions loom much more impactful to not only you, but the other important people in your life.

Deciding to get out of the Active Duty Air Force was a pretty epic decision. It happened as a few things all came together at the same time. One thing was work. I had just had a really great year as probably one of the top Radar Navigators (Bombardier) in our unit: I had gone to Bomb Comp, then been selected to participate in two Strategic Air Command Bombing/Navigation competitions, and we had brought back trophies from both. I was on Stan/Eval, and things were good. Then we had an inspection team come to town, and on the closed book Bold Face test, they switched the order of a couple questions, and I put the responses out of order, and I failed. As an Evaluator. I was devastated.

At the same time I was getting pretty close to finishing my Masters in Business Administration. So in the back of my mind, I had a pretty high confidence in my salability in the outside world. Great education, proven record of success as a junior military officer, etc.

I had been at Griffiss for 3+ years and it was time to think about what came next. As an evaluator and instructor, the path forward for a mid-level Captain was pretty clear: Castle AFB, CA to be a training unit instructor for newbies, or to Offutt AFB, Nebraska to go work in the vault as a planner. Neither job appealed to me after being at the tip of the spear (so to speak) for the past 6 years. Plus, after being an Evaluator and on all the bombing competitions, I felt I had pretty much done everything that really mattered as a B-52 Navigator. (I think I had a pretty narrow viewpoint back then, but I was 29…)

I also had a family to think about. Laura had managed to get assigned to Griffiss a year after I got there, but the opportunities for the two of us being assigned together were quickly dwindling as she moved up in the weather world, and I moved around in the flying world. She had an opportunity to run a weather Detachment in Colorado Springs, but when I tried to get assigned nearby at the Academy as an Instructor, all the logical slots were already filled with guys in my year group who moved there after their first assignment. No openings.

By this time we knew that Jill was on the way, so the search for “what comes next” became more poignant. I didn’t want to commute to see my family, and Laura didn’t want to be an “Air Force Wife,” following her husband around. The timing wasn’t optimum, but it seemed pretty obvious, the time to pull the ejection trigger ring had come. So I put my papers in at the end of November, 1989; Laura followed suit (after I told her); and we left the Air Force together on the 1st of May, 1990.

As it turned out, once we moved to Pittsburgh, I caught on at Cooper Power Systems in Cannonsburg, fairly quickly. I didn’t like the Quality Engineer job at first, but it grew on me the more things I got involved with and the more people I met. Unfortunately, after about a year and a half, the workers went on strike and I got laid off (Not Quality Control needed if they aren’t making anything). So I went “full-time” back to flying with the Reserves, and loved it. When, after more than a year, the strike was settled and they called me back to work, I decided not to go back. I don’t think that was very popular with Laura - we had two kids by then, and had had a couple of healthcare scares. I just had a feeling that the company wouldn’t last, and it turned out they didn’t. About three years later, Corporate closed the place.

At the Reserves, the flying was great… Hurricane relief missions (Hurricane Andrew), Gulf War clean-up, Bosnia twice, lots of South American counter drug missions, Red Flag, Maple Flag in Canada, OREs/ORIs (Readiness Inspections) kept me really busy. Then one day they announced the good times were over and I quickly realized I needed a real job. I looked at several things, including selling lighting with Pat, selling investments/stocks with Merrill Lynch, etc. but I really wanted to do something I could see made a difference.

I found a part-time job that worked into full-time with a guy in Cranberry who was a Naval Architect and wanted to build stuff along the rivers. I ran the administration side of the business and worked as a projected manager. Lots of interesting projects until we hit a dry spot and I was basically working for free, still flying for food. About that same time I found a job at US Airways as a ground school instructor, and it felt like a no-brainer: go with the reliability of a major corporation. Working for an airline sounded cool, and it was!

Then 9/11 happened in 2001. After a few false starts, my unit got activated on 3 December, 2003, and I shipped off to the desert on a year’s worth of orders a week or so later.

In the meantime, US Airways consolidated operations, started furloughing instructors and moved the training center to Charlotte.

While I was activated, I fell back in love with military flying operations, and really enjoyed being a full-time aviator. As my orders expired, the Operations Group had an opening for a full-time GS Air Reserve Technician (ART) Navigator, and they offered it to me. I jumped at it. The pay was virtually the same, if not better, and I didn’t have to move or commute. That was an easy decision.

In all, I (we) faced the job change decision several times, and for me it always came down to what was the best thing to do for our family as a whole. Not always simple choices, but in the end they were fairly straight forward ones I never regretted. (It helped that I got to do everything I ever wanted, work-wise.)

A change decision is pretty easy when you are single. Anything you decide is something only you have to deal with. Get married and have a family, the decisions loom much more impactful to not only you, but the other important people in your life.

Deciding to get out of the Active Duty Air Force was a pretty epic decision. It happened as a few things all came together at the same time. One thing was work. I had just had a really great year as probably one of the top Radar Navigators (Bombardier) in our unit: I had gone to Bomb Comp, then been selected to participate in two Strategic Air Command Bombing/Navigation competitions, and we had brought back trophies from both. I was on Stan/Eval, and things were good. Then we had an inspection team come to town, and on the closed book Bold Face test, they switched the order of a couple questions, and I put the responses out of order, and I failed. As an Evaluator. I was devastated.

At the same time I was getting pretty close to finishing my Masters in Business Administration. So in the back of my mind, I had a pretty high confidence in my salability in the outside world. Great education, proven record of success as a junior military officer, etc.

I had been at Griffiss for 3+ years and it was time to think about what came next. As an evaluator and instructor, the path forward for a mid-level Captain was pretty clear: Castle AFB, CA to be a training unit instructor for newbies, or to Offutt AFB, Nebraska to go work in the vault as a planner. Neither job appealed to me after being at the tip of the spear (so to speak) for the past 6 years. Plus, after being an Evaluator and on all the bombing competitions, I felt I had pretty much done everything that really mattered as a B-52 Navigator. (I think I had a pretty narrow viewpoint back then, but I was 29…)

I also had a family to think about. Laura had managed to get assigned to Griffiss a year after I got there, but the opportunities for the two of us being assigned together were quickly dwindling as she moved up in the weather world, and I moved around in the flying world. She had an opportunity to run a weather Detachment in Colorado Springs, but when I tried to get assigned nearby at the Academy as an Instructor, all the logical slots were already filled with guys in my year group who moved there after their first assignment. No openings.

By this time we knew that Jill was on the way, so the search for “what comes next” became more poignant. I didn’t want to commute to see my family, and Laura didn’t want to be an “Air Force Wife,” following her husband around. The timing wasn’t optimum, but it seemed pretty obvious, the time to pull the ejection trigger ring had come. So I put my papers in at the end of November, 1989; Laura followed suit (after I told her); and we left the Air Force together on the 1st of May, 1990.

As it turned out, once we moved to Pittsburgh, I caught on at Cooper Power Systems in Cannonsburg, fairly quickly. I didn’t like the Quality Engineer job at first, but it grew on me the more things I got involved with and the more people I met. Unfortunately, after about a year and a half, the workers went on strike and I got laid off (Not Quality Control needed if they aren’t making anything). So I went “full-time” back to flying with the Reserves, and loved it. When, after more than a year, the strike was settled and they called me back to work, I decided not to go back. I don’t think that was very popular with Laura - we had two kids by then, and had had a couple of healthcare scares. I just had a feeling that the company wouldn’t last, and it turned out they didn’t. About three years later, Corporate closed the place.

At the Reserves, the flying was great… Hurricane relief missions (Hurricane Andrew), Gulf War clean-up, Bosnia twice, lots of South American counter drug missions, Red Flag, Maple Flag in Canada, OREs/ORIs (Readiness Inspections) kept me really busy. Then one day they announced the good times were over and I quickly realized I needed a real job. I looked at several things, including selling lighting with Pat, selling investments/stocks with Merrill Lynch, etc. but I really wanted to do something I could see made a difference.

I found a part-time job that worked into full-time with a guy in Cranberry who was a Naval Architect and wanted to build stuff along the rivers. I ran the administration side of the business and worked as a projected manager. Lots of interesting projects until we hit a dry spot and I was basically working for free, still flying for food. About that same time I found a job at US Airways as a ground school instructor, and it felt like a no-brainer: go with the reliability of a major corporation. Working for an airline sounded cool, and it was!

Then 9/11 happened in 2001. After a few false starts, my unit got activated on 3 December, 2003, and I shipped off to the desert on a year’s worth of orders a week or so later.

In the meantime, US Airways consolidated operations, started furloughing instructors and moved the training center to Charlotte.

While I was activated, I fell back in love with military flying operations, and really enjoyed being a full-time aviator. As my orders expired, the Operations Group had an opening for a full-time GS Air Reserve Technician (ART) Navigator, and they offered it to me. I jumped at it. The pay was virtually the same, if not better, and I didn’t have to move or commute. That was an easy decision.

In all, I (we) faced the job change decision several times, and for me it always came down to what was the best thing to do for our family as a whole. Not always simple choices, but in the end they were fairly straight forward ones I never regretted. (It helped that I got to do everything I ever wanted, work-wise.)

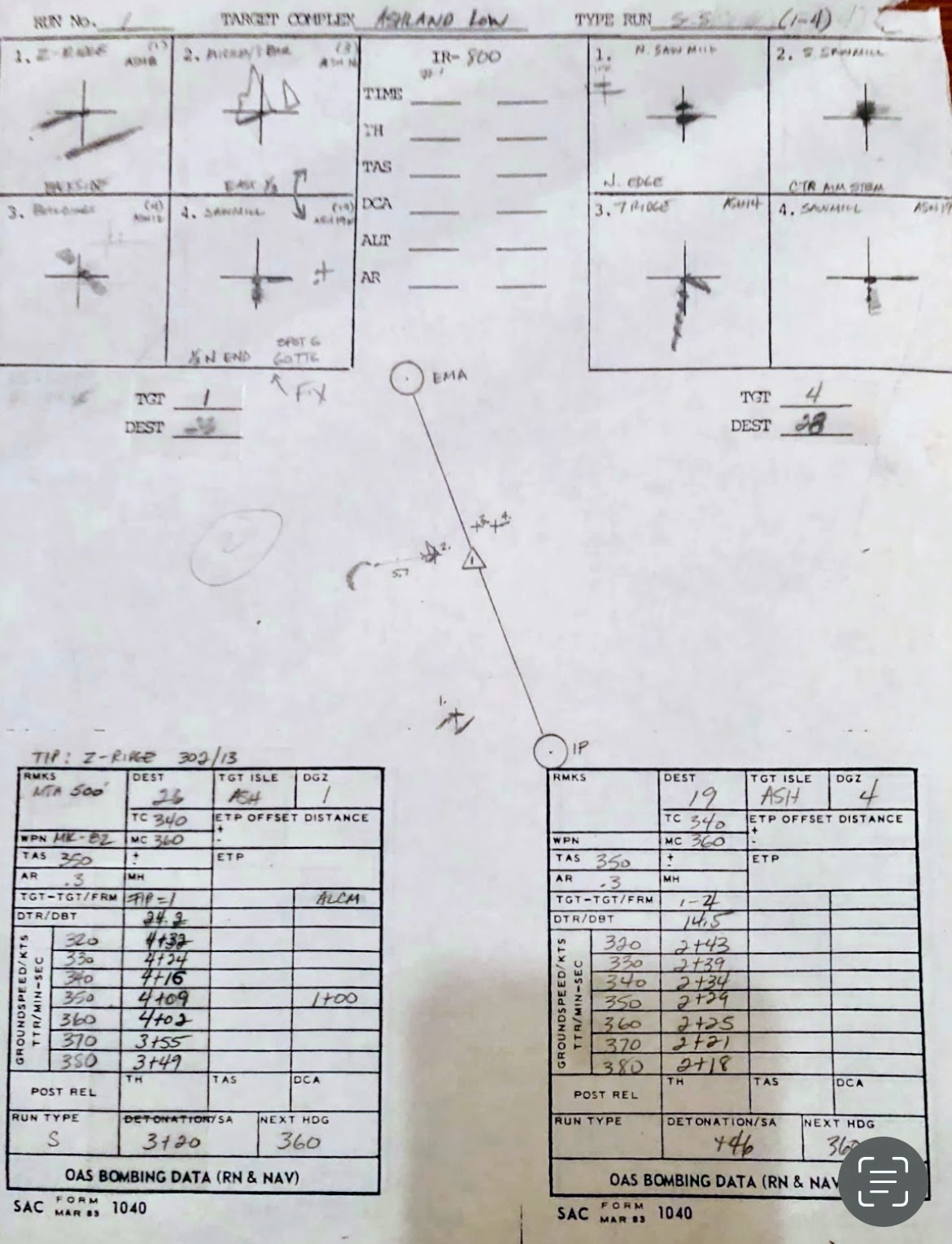

One of my Bomb Run timing/radar aiming forms.